BACK IN 1995 (PC)

When games seek to embrace the various quirks and limitations of an earlier time, they tend to do so from a rose-tinted perspective. This is perfectly reasonable: players expect quality of life improvements, so the fingerprint of older consoles becomes watered down amidst higher screen resolutions, smoother controls, faster frame rates and the like. I mention this because Back in 1995 marks a strange exception to the rule. It’s a warts ‘n’ all love letter to survival horror’s glory days, wallowing a little too thoroughly amidst self-defined limitations. Rather than painting an overly idealised view of the games that inspired it, Throw the Warped Code Out’s throwback remembers them as awash with crippling technical issues. It ends up less a glorified embodiment of the genre’s best bits and more a reminder of the second-tier horror games that got things wrong.

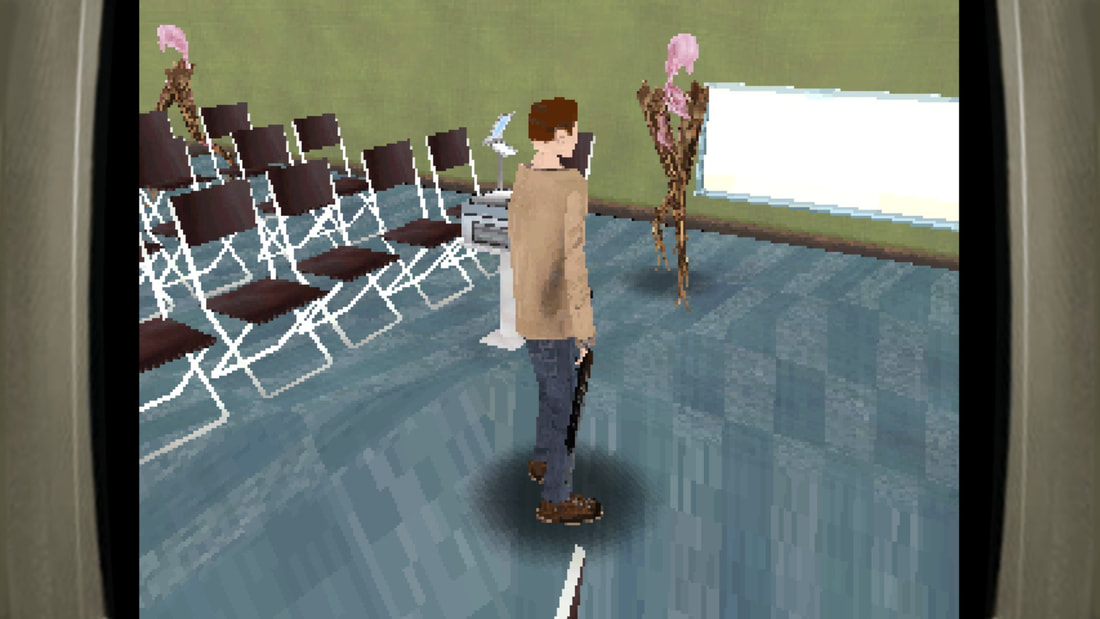

Everything in Back in 1995 is a little creaky. There’s a distinct lack of quality, whilst the execution of its ideas is patchy at best. Whilst broken door locks, claustrophobic camera pans and occasional numeric puzzles have it dreaming of Silent Hill, the grotty, brown environs, rubbish-looking enemies and incredibly stiff controls see it retreading the altogether less alluring realities of Martian Gothic and Evil Dead: Hail to the King.

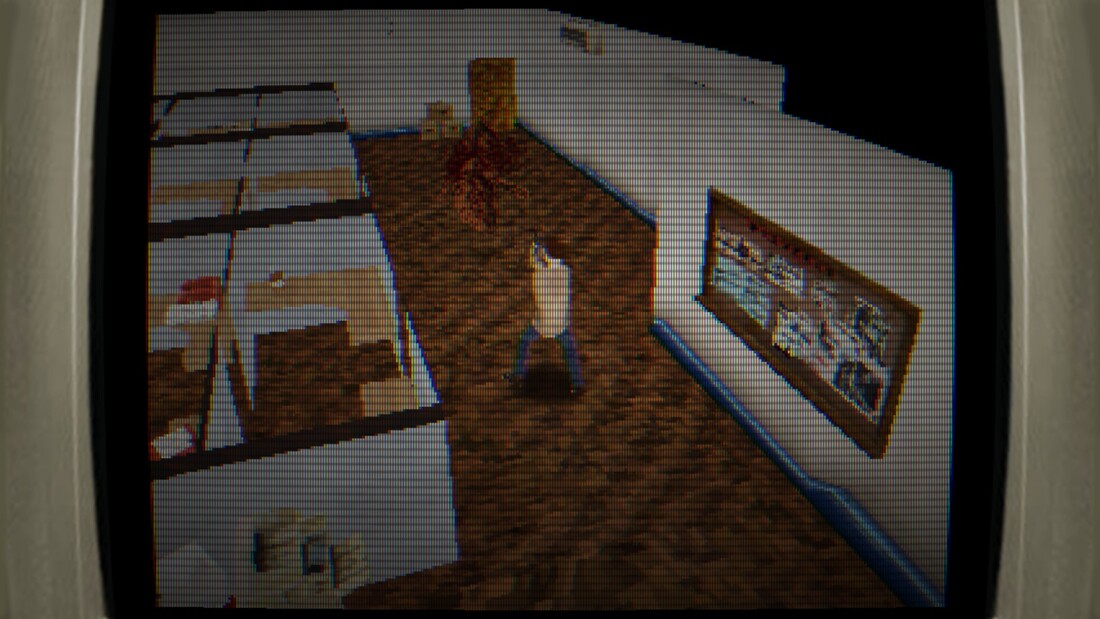

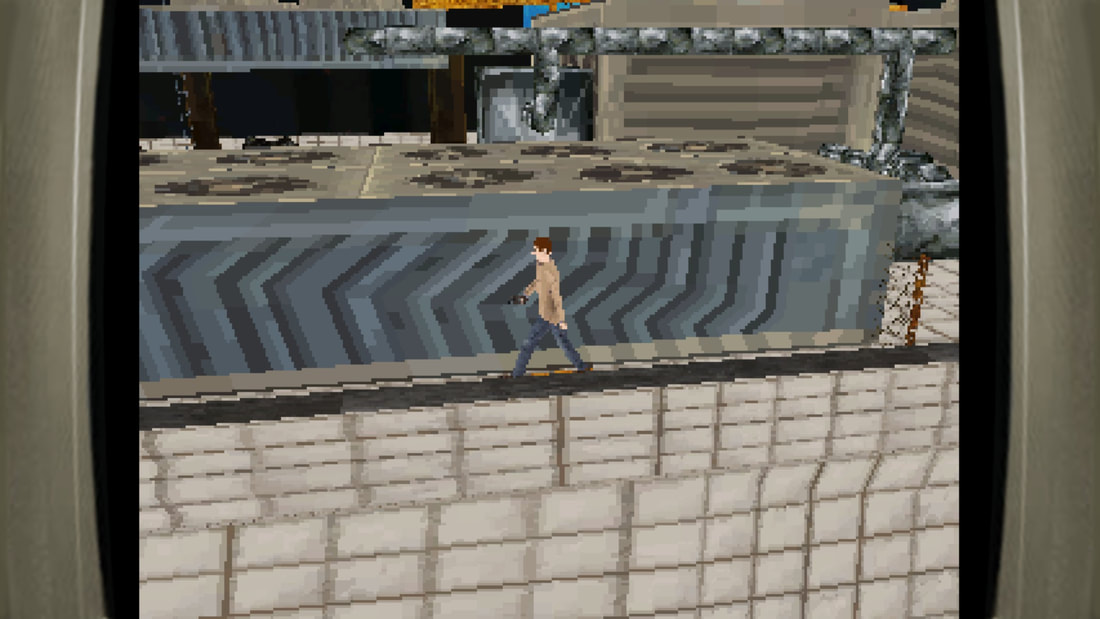

Leaving the CRT on results in a muddied, unclear visual experience...

Even the year it references in its title seems a misnomer. Before even the first Resident Evil had landed, before the phrase ‘survival horror’ had been attributed to such games and in a time when Alone in the Dark could best be considered a cult success amongst MS-DOS aficionados. As the player progresses, it becomes evident that the game sinks under its constraints.

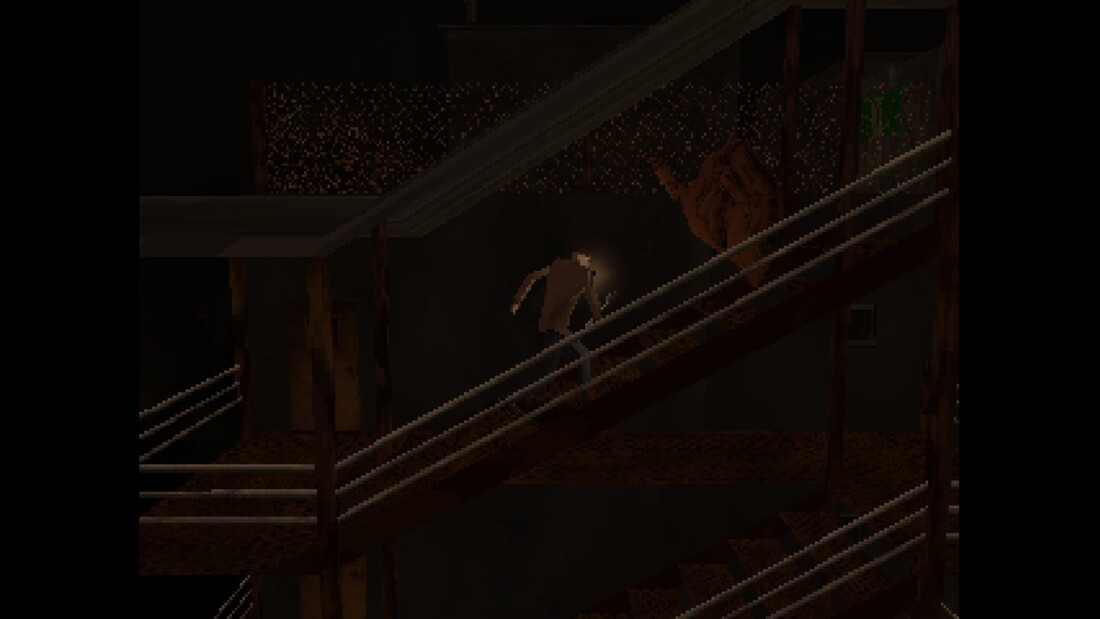

Bringing back tank controls was a smart move; making them heavier than they were even in the earliest survival horror titles was not. Reviving the creepy, voyeuristic camera angles was a good move; the absence of a run function and some incredibly slow combat animations, less so. Like the Silent Hill series, Back in 1995 employs its creations and its environments as externalisations of its troubled lead, Kent, who’s voicing sounds like Joe from Family Guy.

Bringing back tank controls was a smart move; making them heavier than they were even in the earliest survival horror titles was not. Reviving the creepy, voyeuristic camera angles was a good move; the absence of a run function and some incredibly slow combat animations, less so. Like the Silent Hill series, Back in 1995 employs its creations and its environments as externalisations of its troubled lead, Kent, who’s voicing sounds like Joe from Family Guy.

FOCAL POINT: HOW IT SHOULD HAVE BEEN?

Whilst Back in 1995 stumbles to its rather abrupt conclusion after just a couple of hours, the ending leads to a surprising additional scenario. Starting the game a second time, everything appears as before, until Kent encounters a flashlight inescapably reminiscent of Harry Mason’s from Silent Hill. Turning it on results in a lifting of the veil, as the lead character discovers a grimmer reality than what we experienced from the main story, with previously visited locations joined with greater cohesion. This sequence culminates, after around ten minutes of exploring, in a more complete ending. It offers a fleeting glimpse of an altogether darker, more foreboding Back in 1995 that might have been. It’s a more unnerving experience than the main story. Granted, the flashlight approach wouldn’t have fixed the game’s numerous design and technical issues, but it might have made for a more convincing horror experience.

The trouble is, when drawing parallels with one of the cleverest series in all of gaming in terms of psychology, Back in 1995 comes off a very distant second best. Whilst there’s the odd newspaper clipping and one or two cryptic characters, they’re not interesting enough, articulate enough or fleshed-out enough to convey deeper meaning. Any attempts at scenic dualities of meaning feel as though they’ve been achieved with far greater impact and subtly, a long time ago. This is one of many instances where retreading old ground doesn’t win the game any points, because it doesn’t add anything to the canon and appears to misremember (or at least, misrepresent) the appeal the genre held.

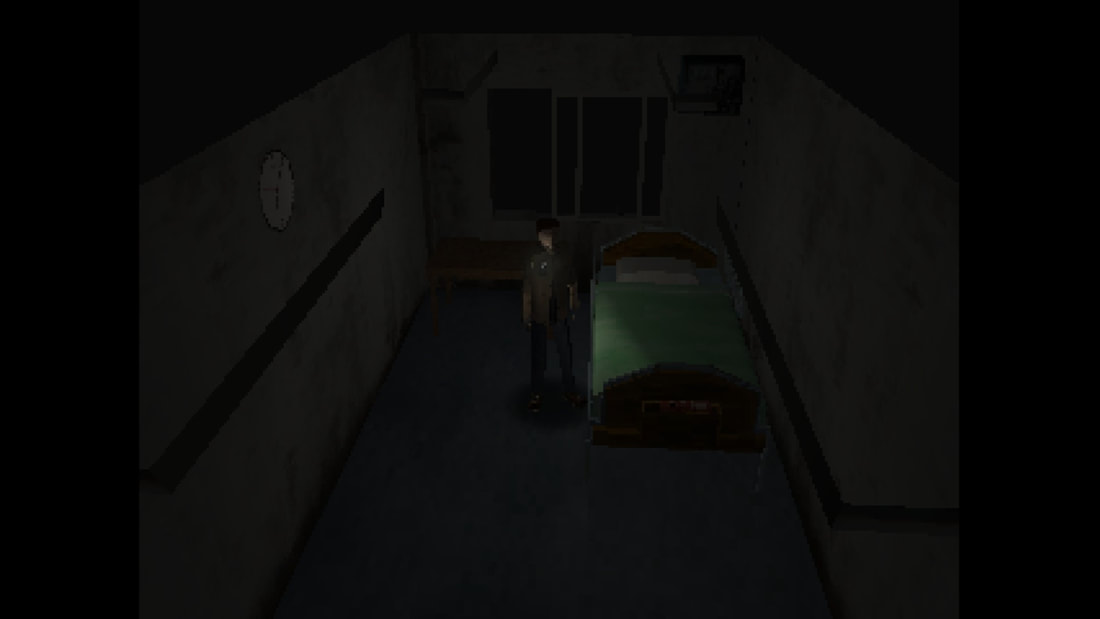

A perfect example is its CRT filter. Both the active filters are severe, making for a dark, muddied and unsteady visual effect far worse than how games looked during the mid-nineties. The problem is that turning off the filter exposes the game as a mess of jagged pixels. It’s an absolute eye-sore, with almost nothing in the way of interesting scenery. Inexplicably, switching off the filter also makes the game garishly bright, robbing it of what little atmosphere the music tries desperately to kindle. Then there’s texture warping, something particularly familiar to PlayStation owners. Back in 1995 emulates this with a degree of success but like so many of its faux-foibles, dramatically overemphasises its effect. Entire structures bulge and contract as Kent passes like he’s in a hall of mirrors.

A perfect example is its CRT filter. Both the active filters are severe, making for a dark, muddied and unsteady visual effect far worse than how games looked during the mid-nineties. The problem is that turning off the filter exposes the game as a mess of jagged pixels. It’s an absolute eye-sore, with almost nothing in the way of interesting scenery. Inexplicably, switching off the filter also makes the game garishly bright, robbing it of what little atmosphere the music tries desperately to kindle. Then there’s texture warping, something particularly familiar to PlayStation owners. Back in 1995 emulates this with a degree of success but like so many of its faux-foibles, dramatically overemphasises its effect. Entire structures bulge and contract as Kent passes like he’s in a hall of mirrors.

Kent looks awful, worse than any lead character I can remember from a comparable title. The game’s floating potato enemies are also absurd. They lack any sense of threat, either as a ‘fright’ or in terms of harming the player, as for the most part, they trundle around in circles. Whilst the locations feel sparse, it’s the occasional puzzles and simpler nods to survival horror’s lineage that provide sporadic highlights. Little things, such as checking your inventory, or admiring the rotating, 3D interpretations of items and ammo the player collects, prove more appropriate reminders of the time.

Back in 1995 can be finished in its entirety in a little over two hours and considerably less than this once you’ve worked out the layouts and puzzles. A secondary ending is a nice touch but adds only another ten minutes or so to the run time and after that, there’s little incentive to return.

Back in 1995 can be finished in its entirety in a little over two hours and considerably less than this once you’ve worked out the layouts and puzzles. A secondary ending is a nice touch but adds only another ten minutes or so to the run time and after that, there’s little incentive to return.

...whilst turning the CRT effect off makes everything look jagged, a lot brighter and therefore, less atmospheric

By failing to conjure the scares or the thematic depth of the nineties classics it’s inspired by, Back in 1995 comes across less as a homage and more as a pastiche of classic survival horror. It grossly overplays the genre’s mechanical difficulties, without managing to recapture the essence of the spooky soundtracks, thought-provoking narratives and labyrinthine environment such games were best remembered for. Whilst the idea was tackled with good intentions, the game falls well short in the quality stakes. A weak reminder of a fantastic genre, you’re better off reliving the nineties originals.