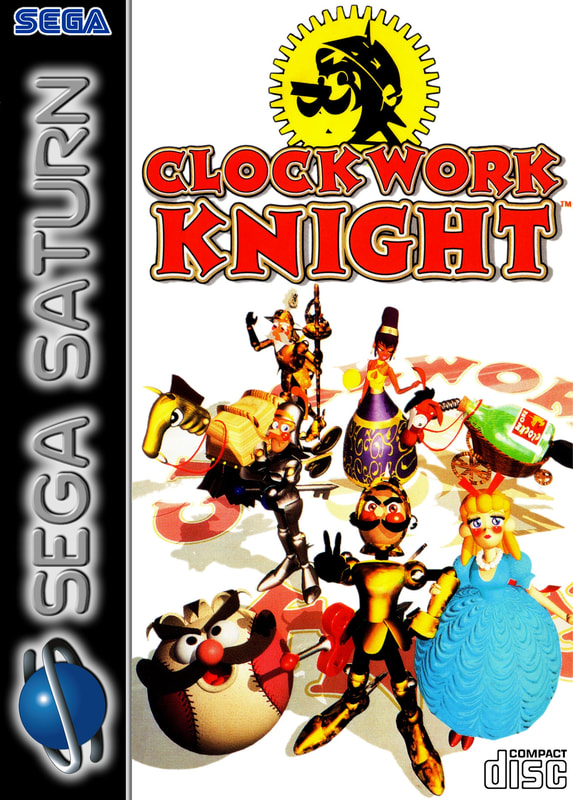

CLOCKWORK KNIGHT (SAT)

Thanks in large part to Donkey Kong Country, gaming played host to a brief but concerted craze for a particular kind of platformer during the mid-nineties. Namely, that which utilised 2D digitised sprites deriving from high-resolution 3D models. If you had a video game system during the period, then chances are at least one developer will have tried their hand at this technique. Indeed, Saturn owners in Europe had to wait no time at all for such a game, as Clockwork Knight released alongside Daytona USA and Virtua Fighter at the console’s launch.

SEGA’s 2D platformer would prove a solid but unexciting entry to a heavily subscribed genre. Those expecting to witness new frontiers afforded by the 32-bit hardware, or even a platformer to rival the best and brightest the Mega Drive had to offer, would come away disappointed. Clockwork Knight lacks the dynamism of the Sonic games, whilst its level design misses the tightness and creativity of the Illusion titles. But for its polygonal bosses and a smattering of video sequences, there’s little to mark CK out as Saturn-specific software. That said, if you can overlook its gaudy presentation, there’s a solid platformer in here, and one that brought to life enlarged, domestic environments before Toy Story.

Whilst there's plenty of colour to Clockwork Knight, its gameplay struggles to get the pulse racing

Central protagonist Pepperouchau (we’ll go with Pepper from here onwards) begins a journey through four sections of a house as he heads for the attic and his beloved Chelsea, who has been kidnapped. Armed with a wind-up key, Pepper must navigate a host of platforming obstacles and wacky enemies, accruing currency for bonus stages, beating the (fairly lenient) time limits and collecting a selection of keys placed around each stage. The opening levels begin in a fairly straightforward fashion, allowing the player to acclimatise to a very simple control scheme: jump and attack, along with a directional double-tap that allows Pepper to run, something you’ll find crucial for boss fights. The control response times are fairly good, with relatively few deaths resulting from dud inputs.

A pair of bedrooms form the initial stages. Betsy’s consists mainly of scaling building blocks, completing simple block-pushing tasks and avoiding collapsing doll’s houses. Kevin’s bedroom is similar at first glance, but a little more perilous, seeing Pepper ride the top of a toy train, jumping obstructions and taking out the odd toy helicopter. It’s like a less high-octane equivalent to the mine-cart sequences seen in Taz Mania and Donkey Kong Country. It’s okay, but rather safe and sedate. Though not all games need to be trailblazers, they do need to deliver at least a modicum of excitement and creativity. Sometimes, Clockwork Knight feels like it’s going through the motions.

A pair of bedrooms form the initial stages. Betsy’s consists mainly of scaling building blocks, completing simple block-pushing tasks and avoiding collapsing doll’s houses. Kevin’s bedroom is similar at first glance, but a little more perilous, seeing Pepper ride the top of a toy train, jumping obstructions and taking out the odd toy helicopter. It’s like a less high-octane equivalent to the mine-cart sequences seen in Taz Mania and Donkey Kong Country. It’s okay, but rather safe and sedate. Though not all games need to be trailblazers, they do need to deliver at least a modicum of excitement and creativity. Sometimes, Clockwork Knight feels like it’s going through the motions.

Things get a little more adventurous when the action reaches the Kitchen. Slippery surfaces require a level of care and there’s a neat section that sees sponges and other household items act as a shifting bridge within a sink of fluctuating water levels. It has to be said, however, that similar concepts were delivered with a fair bit more pizazz in older Mega Drive platformers Cool Spot and World of Illusion. The final platforming setting is the Attic, which although the most drab-looking level, does offer the most challenging platforming and some trickier enemies.

The boss fights feel like a missed opportunity. There’s no question, they’re a very strange mix, including what appears to be a mech toy, a chef who rolls around with a pot on his head, and a sentient television. These foes mostly function alright, in a familiar, trial-and-error kind of way. However, encounters play out on quite uninspired, flat and featurelesss surfaces. The boss designs miss the mark, and though they utilise 3D polygons and transition between layers (something which adds little to the gameplay), they’re pretty forgettable.

The boss fights feel like a missed opportunity. There’s no question, they’re a very strange mix, including what appears to be a mech toy, a chef who rolls around with a pot on his head, and a sentient television. These foes mostly function alright, in a familiar, trial-and-error kind of way. However, encounters play out on quite uninspired, flat and featurelesss surfaces. The boss designs miss the mark, and though they utilise 3D polygons and transition between layers (something which adds little to the gameplay), they’re pretty forgettable.

Some instances of 3D models transitioning between layers can be seen in the train sequences and the boss battles

Pepper acts as a mirror of the game’s problems. He’s the polar opposite of Sonic. Maybe that was the point, to offer something concertedly different to what SEGA was known for at the time. Whatever the thinking, the toy soldier comes across as dull and unmemorable. Gamers would unlikely have been won over by a protagonist that has none of the charisma and cool of Sonic, whilst his lack of distinctive abilities is emblematic of the game’s stilted creativity. Whilst solidly crafted, the gameplay feels dated and old-fashioned, probably the last descriptors early adopters will have wanted to hear bandied around a console launch. Aside from being the only platformer available to Saturn gamers at the time, it’s hard to think of a genuine selling point.

Visually the game certainly isn’t lacking for detail, with a huge array of nice touches to be found, including instances of activity transitioning between layers, such as when a model train rounds a corner from the background to link up with the playing space. However, its crunched-looking sprites and garish colour schemes are distinctly unattractive. As mentioned with some of the bosses, the art style is generally dubious and the attract screens look horrible. The sound effects have a bit of pop to them, though some repetitive noises (most notably after beating one of the bosses) are hideous.

Visually the game certainly isn’t lacking for detail, with a huge array of nice touches to be found, including instances of activity transitioning between layers, such as when a model train rounds a corner from the background to link up with the playing space. However, its crunched-looking sprites and garish colour schemes are distinctly unattractive. As mentioned with some of the bosses, the art style is generally dubious and the attract screens look horrible. The sound effects have a bit of pop to them, though some repetitive noises (most notably after beating one of the bosses) are hideous.

Launching near the end of an era where players were encouraged to play through their platformers in a single sitting, CK’s lean collection of 13 levels amount to a little under an hour’s play, depending on how much trouble a couple of bosses cause. Three difficulty settings mean there’s at least a handful of sessions of play to glean from it. Reasonable escapism with no glaring flaws, but no real triumphs either. Little of Clockwork Knight will live long in the memory. A functional but underwhelming Saturn launch title.