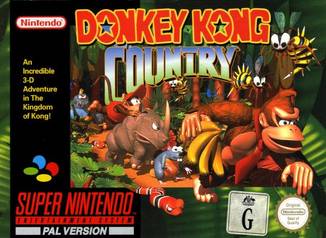

DONKEY KONG COUNTRY (SNES)

With Mario having emerged as Nintendo’s go-to star for platforming (and for that matter, most other genres), Donkey Kong was relegated to the side-lines for more than a decade, before the gorilla was at last given another shot at the big-time in 1994. With development duties being handed to Rare and the prospect of state-of-the-art visuals, the SNES looked on course for another golden platformer.

And at face-value, all seemed well. Both audio and visuals are outstanding, the gameplay sticks close to Nintendo’s celebrated platforming blueprint, and there’s a wealth of levels that ensure it won’t be finished overnight. But scratch the surface, and you’ll find what was, in hindsight, a bit of a disappointment; a case of what might have been. It’s the first Donkey Kong not to be overseen by Shigeru Miyamoto (though he did work with Rare on the project), and whilst it makes for a fairly convincing mimic of Super Mario World early on, frustrating level-design and unforgiving gameplay mean Donkey Kong Country struggles to conjure the same satisfying gameplay experience.

The opening levels are a pleasure; Donkey Kong and Diddy Kong act as a double-team who the player can switch between via a tap of the A button. There isn’t a great deal of difference between the two; the former is a bit stronger, the latter a little quicker. One hit will remove the ‘active’ character from play, leaving you in control of the other, who remains vulnerable of losing a life until you happen across a DK barrel with which to bring the other back. Otherwise, it’s more or less the exact same configuration as Mario, with B serving as a jump/enemy bop and X to run. It’s brisk, engaging, and replete with bonuses and secrets from the first level onwards.

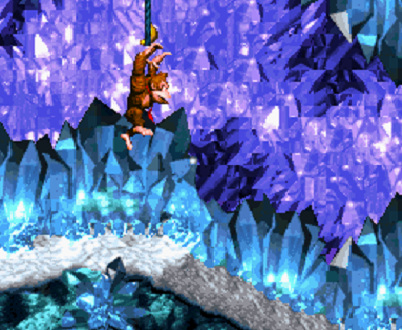

Neither as dynamic as Sonic nor as tightly-designed as Mario, DCK nevertheless follows the tried-and-true platforming route Nintendo spent much of the period honing. There’s no questioning Rare’s endeavour; levels move from the relative comfort of the jungles out into inhospitable, glacial mountains with perilous, slippery terrain; industrial factories and ancient ruins. The pair partake in some fantastic underwater sequences that prove a real stand-out thanks to a breathtakingly beautiful mix of atmospheric music and stunning visual effects. Indeed, the swimming bits are the one element Donkey Kong Country can with some surety claim to trump Mario on. However, cracks begin to emerge with extended play.

Namely that it becomes dishearteningly difficult really quite quickly. It occurred to me that the first few levels have the sensation of tighter control because you aren’t tasked with making pixel-perfect jumps or mixing the hazardous run/jump functions together which, when combined with tiny ledges, are a recipe for cheap deaths. And it’s absolute deaths-galore in Donkey Kong Country, as each new level presents an undesirable mix of uncompromising platform challenges which leave precious little room for error, a glut of foes, and seemingly the need for a near-Godlike level of prescience in evading deadly obstacles. There’s a number of ride-the-mine-cart sequences, the kind that were a by-word for frustration during the 16-bit era (remember Taz-Mania?), whilst a muddled save/backtrack system doesn’t help matters either.

I ended up dying scores of times per level by the fourth world, thus becoming familiar with regular Game Over screens and much replaying of levels. You would imagine it wouldn’t be the smartest move to place pixel-perfect jumps right at the end of a run of difficult levels (by which point the gamer has become well and truly addled anyway) that preceded a save point, yet time and again, it was deemed appropriate. Caution is fatal as it often leads to missing a platform or losing the momentum needed to traverse chasms. Too proactive, and you’ll shed valuable lives falling off ledges, or go clattering into an enemies headed in your direction at speed. And there are so, so many cheap deaths. Take jumping on snakes for example, if you’re adjudged to have touched the floor fractionally before the foe: instant death. And don’t get me started on evading hornets, fast moving nuisances that bring about death on contact. Rather than going with fresh challenges as you progress, the developer has tended to throw an increasingly dense cluttering of hazards your way, with the odd visual impairment trick thrown in on top, and it all starts to get a bit jading.

Namely that it becomes dishearteningly difficult really quite quickly. It occurred to me that the first few levels have the sensation of tighter control because you aren’t tasked with making pixel-perfect jumps or mixing the hazardous run/jump functions together which, when combined with tiny ledges, are a recipe for cheap deaths. And it’s absolute deaths-galore in Donkey Kong Country, as each new level presents an undesirable mix of uncompromising platform challenges which leave precious little room for error, a glut of foes, and seemingly the need for a near-Godlike level of prescience in evading deadly obstacles. There’s a number of ride-the-mine-cart sequences, the kind that were a by-word for frustration during the 16-bit era (remember Taz-Mania?), whilst a muddled save/backtrack system doesn’t help matters either.

I ended up dying scores of times per level by the fourth world, thus becoming familiar with regular Game Over screens and much replaying of levels. You would imagine it wouldn’t be the smartest move to place pixel-perfect jumps right at the end of a run of difficult levels (by which point the gamer has become well and truly addled anyway) that preceded a save point, yet time and again, it was deemed appropriate. Caution is fatal as it often leads to missing a platform or losing the momentum needed to traverse chasms. Too proactive, and you’ll shed valuable lives falling off ledges, or go clattering into an enemies headed in your direction at speed. And there are so, so many cheap deaths. Take jumping on snakes for example, if you’re adjudged to have touched the floor fractionally before the foe: instant death. And don’t get me started on evading hornets, fast moving nuisances that bring about death on contact. Rather than going with fresh challenges as you progress, the developer has tended to throw an increasingly dense cluttering of hazards your way, with the odd visual impairment trick thrown in on top, and it all starts to get a bit jading.

DKC looks fantastic though, something that shouldn’t be taken lightly in an era where pre-rendered sprites and 3D objects were notoriously hit-and-miss. Donkey and Diddy are extremely impressive, not only for the level of detail they exude, but also the impressive fluidity of the animation, allowed for through Rare’s pioneering compression technique that copes with plenty of activity and high-end animations within the SNES’s memory constraints. The jungles and the plump green trees are lush and smart, whilst throughout the game you’ll be faced with torch-lit caverns, mountains obscured in blizzards and lightning-bolt rainstorms. The underwater sections are, at times, sensational showpieces. Perhaps a result of the expensive graphics engine and large quantity of levels there’s a noticeable degree of recycling; mines, reefs and jungle templates share a certain familiarity that can’t entirely be glossed-over with palette swaps, the same being the case for the enemies. Likewise, the solid, quick-fire boss fights are diminished somewhat by the strange, underwhelming and dingy banana-filled rooms in which they all take place. Overall though, it looks stunning.

The music is similarly top-draw. It’s a very complete soundtrack; funky, laid-back jungle beats, infectious title screen and life-loss jingles, frantic boss themes, ominous vibes accompanying the mine levels and powerful, affecting thrums give real volume to the underwater segments. Donkey Kong Country doesn’t miss a beat, with sharp sound effects providing an able accompaniment.

Donkey Kong Country has everything it needed to have become a premier platforming experience. Every facet of its presentation is top-draw, there are loads of levels, and many of them in isolation make for decent gaming with plenty of attention-to-detail. Skittish controls, unfair deaths and increasingly-torturous treks toward the sanctuary of the next save point will likely break the will of many a gamer used to the immaculate (and crucially, more forgiving) Mario titles. A good game, but strictly one for the platforming tough-nut.

The music is similarly top-draw. It’s a very complete soundtrack; funky, laid-back jungle beats, infectious title screen and life-loss jingles, frantic boss themes, ominous vibes accompanying the mine levels and powerful, affecting thrums give real volume to the underwater segments. Donkey Kong Country doesn’t miss a beat, with sharp sound effects providing an able accompaniment.

Donkey Kong Country has everything it needed to have become a premier platforming experience. Every facet of its presentation is top-draw, there are loads of levels, and many of them in isolation make for decent gaming with plenty of attention-to-detail. Skittish controls, unfair deaths and increasingly-torturous treks toward the sanctuary of the next save point will likely break the will of many a gamer used to the immaculate (and crucially, more forgiving) Mario titles. A good game, but strictly one for the platforming tough-nut.

PIXEL SECONDS: DONKEY KONG COUNTRY (SNES)

From the moment I saw the intro screen, a broad smile spread across my face as I immersed myself in the difficult and demanding terrain of Donkey Kong Country. The homage to the original theme, rudely interrupted be DK himself made me smile, and that’s what the rest of the game does with the odd enforced grimace here and there. I agree with Tom’s sentiments about the difficulty of the later levels, the practice and precision required for success is very challenging. I can also understand why this may turn many a gamer off, experienced such as TC or otherwise. However, growing up on a diet of near-impossible arcade platformers, beaters and shooters, and 8-bit hard cases where handling the responsiveness and slow-down was a task in itself; I found DKC an enjoyable escapade. The graphics are simply exquisite for a 16-bit platform, as is the sound, and even though the controls and positioning can be unforgiving and pernickety at times, I found this a nice colourful challenge in an environment away from other typical platform ventures. I do concede that the lack of restart points is an issue, and some parts, such as the barrel blast section are exceptionally frustrating. For some reason though, I never found this as annoying as to detract massively from the game as a whole. No, it’s not Mario or Sonic, but a solid and great looking effort [8] – Chris Weatherley © 2012

From the moment I saw the intro screen, a broad smile spread across my face as I immersed myself in the difficult and demanding terrain of Donkey Kong Country. The homage to the original theme, rudely interrupted be DK himself made me smile, and that’s what the rest of the game does with the odd enforced grimace here and there. I agree with Tom’s sentiments about the difficulty of the later levels, the practice and precision required for success is very challenging. I can also understand why this may turn many a gamer off, experienced such as TC or otherwise. However, growing up on a diet of near-impossible arcade platformers, beaters and shooters, and 8-bit hard cases where handling the responsiveness and slow-down was a task in itself; I found DKC an enjoyable escapade. The graphics are simply exquisite for a 16-bit platform, as is the sound, and even though the controls and positioning can be unforgiving and pernickety at times, I found this a nice colourful challenge in an environment away from other typical platform ventures. I do concede that the lack of restart points is an issue, and some parts, such as the barrel blast section are exceptionally frustrating. For some reason though, I never found this as annoying as to detract massively from the game as a whole. No, it’s not Mario or Sonic, but a solid and great looking effort [8] – Chris Weatherley © 2012