Q&A: WIP3OUT (PS)

WAYNE IMLACH, LEAD DESIGNER, PSYGNOSIS LEEDS

"Wip3out was one of the quickest, most stylish and most challenging games of its era. Tom and Chris quiz the game's lead designer, Wayne Imlach, on split-screen triumphs, the difficulties of following WipEout 2097, and pushing the PlayStation to its limits" Posted 4th March 2015.

By Tom Clare & Chris Weatherley © 2015 |

|

This may come as a surprise you all, but we at The Pixel Empire are rather partial to Wip3out. Tom scored it a perfect '10' in his review, only to then get unceremoniously beaten up by Chris in a titanic Hi-Score Duel on Stanza Inter. All that was left to do was delve a little deeper into the back-story of this remarkable futuristic racer. And what better way to do so than a Q&A with Wayne Imlach, the game's lead designer?

|

Wip3out was Leeds Studio's first game. What were your goals at the outset?

Wip3out was the first major title to come out of the Leeds Studio, but it’s a little known fact that two other games preceded it in the Leeds ludography – Global Domination, a tactical wargame played out on a 3D globe of the earth, and Retro Force (fondly remembered as ‘Retro Farce’), a top-down 3D shooter. Neither made a big splash in terms of game release, so it’s understandable that they have been overshadowed by later titles. While the previous games didn’t do much in terms of sales, they did prove that the studio had the technical know-how and management to get titles out the door, so in part they laid the foundations for being given established IP such as Wip3out. |

Of course, along with the IP came some conditions, such as overall budget and release date. These were the things that had the biggest impact on our goals for the project – we had to strike that balance between adding enough in terms of features and technology to stand out from previous WipEout games, but still stay within budget and schedule. With that in mind, we quickly focused on the following areas for development:

Technology: Increase the output resolution for sharper visuals and implement split screen multiplayer support, without sacrificing frame rate.

Gameplay: Smooth out the learning curve and tweak the vehicle physics for less frustration, while making the differences between craft more meaningful.

Art: Create an art style that, while recognisably ‘WipEout’ in style, was distinct enough to be unique to our iteration of the series.

Music: Continue the tradition of using licensed music, but unify the mix of styles and have a more cohesive sound running through the audio.

We pretty quickly hashed out these goals in a few brainstorm sessions among the disciplines, and were lucky to have some very professional and dedicated team leads that understood the realities of development and made a realistic assessment of what we could do in the time. Being a sequel also helped immensely. In effect, the previous games were our ‘prototypes’, so we had a very high degree of confidence about what would work, so avoided any costly and time-consuming pre-production development.

We also knew this would be the last of the WipEouts on the PSone and that Sony Liverpool were working on the next-gen iteration of the series, so we wanted it to ideally be a refinement and ‘peak’ for the series on the platform. So nothing high-risk. In some respects, it was the ‘safest’ of the WipEouts, in both terms of game design and development.

Did the team feel pressure in following WipEout 2097, and was there ever a dialogue between yourselves and Studio Liverpool on the direction the game should take?

There was certainly some trepidation on taking on such a valued IP – but overall the team was always confident we could do the series justice. In part this was down to the experience of the team, some of whom had worked on the earlier incarnations in the series and were comfortable with the game aesthetic. From the design side, I think it was mainly an inflated sense of self-confidence on my part, as I had personally never had to design any type of racing game before then (though did count the genre as one of my favourite game types). It helped that the fundamental game rules had already been established, so it was more about leveraging and refining the original design. Luckily the decisions we made turned out to be sound choices in the long run.

I don’t recall much direction being given from the Liverpool Studio, aside from perhaps some support in technical queries – I can only presume there was enough trust in the Leeds Studio to maintain the game ethos and overall quality. Perhaps their focus on developing the ‘next gen’ PS2 version (WipEout Fusion) also worked to our advantage, moving attention away from our own take on the series. Either way, we were left to quietly get on with creating this last hurrah for the PS1.

Technology: Increase the output resolution for sharper visuals and implement split screen multiplayer support, without sacrificing frame rate.

Gameplay: Smooth out the learning curve and tweak the vehicle physics for less frustration, while making the differences between craft more meaningful.

Art: Create an art style that, while recognisably ‘WipEout’ in style, was distinct enough to be unique to our iteration of the series.

Music: Continue the tradition of using licensed music, but unify the mix of styles and have a more cohesive sound running through the audio.

We pretty quickly hashed out these goals in a few brainstorm sessions among the disciplines, and were lucky to have some very professional and dedicated team leads that understood the realities of development and made a realistic assessment of what we could do in the time. Being a sequel also helped immensely. In effect, the previous games were our ‘prototypes’, so we had a very high degree of confidence about what would work, so avoided any costly and time-consuming pre-production development.

We also knew this would be the last of the WipEouts on the PSone and that Sony Liverpool were working on the next-gen iteration of the series, so we wanted it to ideally be a refinement and ‘peak’ for the series on the platform. So nothing high-risk. In some respects, it was the ‘safest’ of the WipEouts, in both terms of game design and development.

Did the team feel pressure in following WipEout 2097, and was there ever a dialogue between yourselves and Studio Liverpool on the direction the game should take?

There was certainly some trepidation on taking on such a valued IP – but overall the team was always confident we could do the series justice. In part this was down to the experience of the team, some of whom had worked on the earlier incarnations in the series and were comfortable with the game aesthetic. From the design side, I think it was mainly an inflated sense of self-confidence on my part, as I had personally never had to design any type of racing game before then (though did count the genre as one of my favourite game types). It helped that the fundamental game rules had already been established, so it was more about leveraging and refining the original design. Luckily the decisions we made turned out to be sound choices in the long run.

I don’t recall much direction being given from the Liverpool Studio, aside from perhaps some support in technical queries – I can only presume there was enough trust in the Leeds Studio to maintain the game ethos and overall quality. Perhaps their focus on developing the ‘next gen’ PS2 version (WipEout Fusion) also worked to our advantage, moving attention away from our own take on the series. Either way, we were left to quietly get on with creating this last hurrah for the PS1.

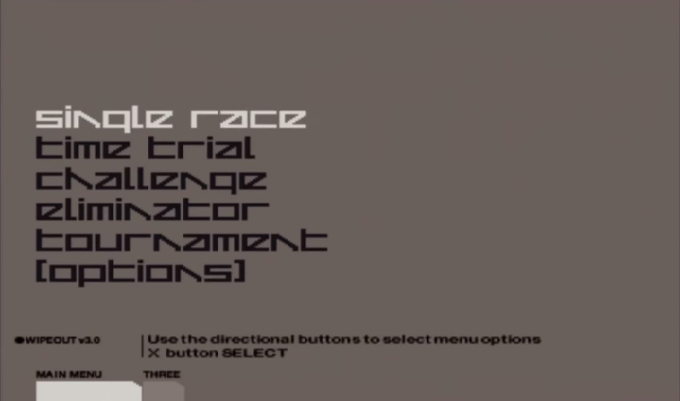

The Designers Republic lent Wip3out distinctive, stylish presentation

The Designers Republic were responsible for elements of Wip3out's unique presentation. How did the collaboration come about, and were their designs a comfortable fit for your vision of the game?

Designers Republic had been involved in the WipEout franchise since its inception, so I think it was only natural to involve them in the visual design for Wip3out. I’m not sure how they first came be involved in the original WipEout – no doubt a chance meeting between a developer and a designer, or perhaps one of the original devs was a fan of their work. Back in the day, it was easy to just reach out to other artists and get them involved in projects in an informal way, letting the relationship grow organically. By the time we came to create Wip3out though, that relationship had matured and was quite intimate – if I recall correctly, members of the art team were good friends with DR artists on a personal level.

I think the clean, iconic designs they provided suited WipEout perfectly – indeed, I’d go as far as to say the style we used for Wip3out (with its cleaner, less garish palette) probably supported the DR aesthetic more so than 2097.

Mega Mall features a remarkable, spiralling descent midway through the course. Was this a tricky effect to achieve, and did any circuit in particular pose difficulties during development?

By the time we came to develop Wip3out, the track design tools were fairly mature. From a purely technical standpoint, the spiral in Mega Mall didn’t pose any particular challenge in of itself, though there was a fair bit of tweaking to get the width and steepness of the slope just right.

Of the remaining tracks, the only one that was somewhat experimental was Manortop, with its sharp turns and gapped track surface. Even there I don’t think there was any special code put in place to support the unusual design – it was simply a ‘feature’ of the way tracks were built and stored that allowed something slightly off the wall like this to exist.

The game was developed in just nine months. Were there any notable ideas or features that had to be cut from the end product?

We were pretty strict with the original design, though there were a few initial ideas that quickly fell to the wayside:

· A special prototype craft that allowed the player to tweak its attributes

· A craft damage model that affected handling

· Several unusual weapon ideas

· Damage to the track itself from collisions and weapon usage

· Qualification laps

· A more involved league system

· Characters in the form of race pilots (a throwback to the original WipEout)

· Some additional visual effects such as heat haze

These were tabled as options, but I don’t think any additional work was ever done – we really didn’t have the time for working on anything that wasn’t 100% going into the game.

Designers Republic had been involved in the WipEout franchise since its inception, so I think it was only natural to involve them in the visual design for Wip3out. I’m not sure how they first came be involved in the original WipEout – no doubt a chance meeting between a developer and a designer, or perhaps one of the original devs was a fan of their work. Back in the day, it was easy to just reach out to other artists and get them involved in projects in an informal way, letting the relationship grow organically. By the time we came to create Wip3out though, that relationship had matured and was quite intimate – if I recall correctly, members of the art team were good friends with DR artists on a personal level.

I think the clean, iconic designs they provided suited WipEout perfectly – indeed, I’d go as far as to say the style we used for Wip3out (with its cleaner, less garish palette) probably supported the DR aesthetic more so than 2097.

Mega Mall features a remarkable, spiralling descent midway through the course. Was this a tricky effect to achieve, and did any circuit in particular pose difficulties during development?

By the time we came to develop Wip3out, the track design tools were fairly mature. From a purely technical standpoint, the spiral in Mega Mall didn’t pose any particular challenge in of itself, though there was a fair bit of tweaking to get the width and steepness of the slope just right.

Of the remaining tracks, the only one that was somewhat experimental was Manortop, with its sharp turns and gapped track surface. Even there I don’t think there was any special code put in place to support the unusual design – it was simply a ‘feature’ of the way tracks were built and stored that allowed something slightly off the wall like this to exist.

The game was developed in just nine months. Were there any notable ideas or features that had to be cut from the end product?

We were pretty strict with the original design, though there were a few initial ideas that quickly fell to the wayside:

· A special prototype craft that allowed the player to tweak its attributes

· A craft damage model that affected handling

· Several unusual weapon ideas

· Damage to the track itself from collisions and weapon usage

· Qualification laps

· A more involved league system

· Characters in the form of race pilots (a throwback to the original WipEout)

· Some additional visual effects such as heat haze

These were tabled as options, but I don’t think any additional work was ever done – we really didn’t have the time for working on anything that wasn’t 100% going into the game.

Was there ever a sense of rivalry between Leeds Studio and Attention To Detail, and were you able to draw inspiration from Rollcage?

I do recall looking at Rollcage when it came out, but I don’t think it was ever considered a rival game. It was quite a different beast to WipEout. We were already well into development by the time Rollcage was published anyhow, so we were past any stage of changing the design to reflect something from another game.

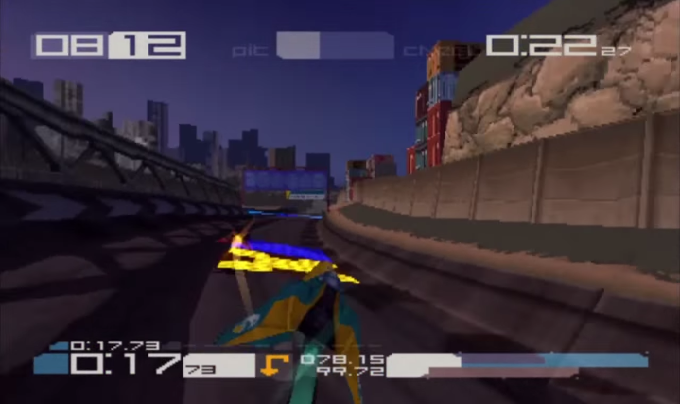

The split-screen two-player was a first for the series and an oft-unheralded success. What compromises had to be made, and were you satisfied with the end result?

The trickiest part of the split-screen was maintaining a good frame rate by culling the scenery just enough to reduce the amount of geometry being drawn, yet maintain sense of immersion in the world. We actually ended up manually editing which objects would be drawn from each ‘tile’ of the track to get the best balance between performance and visuals. Someone would literally drive around the track from tile to tile and remove or add world objects via an in-game editing tool. A fairly time consuming task, but it paid off I think – the game looks great even in split-screen mode and slow-down is minimal.

I do recall looking at Rollcage when it came out, but I don’t think it was ever considered a rival game. It was quite a different beast to WipEout. We were already well into development by the time Rollcage was published anyhow, so we were past any stage of changing the design to reflect something from another game.

The split-screen two-player was a first for the series and an oft-unheralded success. What compromises had to be made, and were you satisfied with the end result?

The trickiest part of the split-screen was maintaining a good frame rate by culling the scenery just enough to reduce the amount of geometry being drawn, yet maintain sense of immersion in the world. We actually ended up manually editing which objects would be drawn from each ‘tile’ of the track to get the best balance between performance and visuals. Someone would literally drive around the track from tile to tile and remove or add world objects via an in-game editing tool. A fairly time consuming task, but it paid off I think – the game looks great even in split-screen mode and slow-down is minimal.

The game featured eight very different crafts, did you have a personal favourite?

I really liked the twin hull, tough, JCB-like look of the Goteki45 ship, though if it came down to racing my favourite was probably the Assegai, which was the nimblest of all the ships.

Phantom speed class is eye-wateringly fast. Did Wip3out push the PSone to its limits?

There was certainly a lot of technical innovation in Wip3out, considering the game ran at a consistent 30fps in hi-res mode within some fairly detailed environments. This was a mix of some very talented programmers on the team, a deep understanding of a console that had been available long enough for all the little development quirks and tricks to be discovered, and some very careful 3D modeling that got maximum bang out of a limited polygon count.

There's been little word on the series since Studio Liverpool's closure in 2012. Do you feel WipEout and futuristic racers as a whole still have a place in modern gaming?

Definitely – these things are usually cyclical. I wouldn’t be surprised if there are plans to resurrect the PS4 version that Liverpool were supposedly working on prior to the closure. The brand has too much value to just ignore. Perhaps something to launch along with Project Morpheus? WipEout plus VR would equal awesome.

I really liked the twin hull, tough, JCB-like look of the Goteki45 ship, though if it came down to racing my favourite was probably the Assegai, which was the nimblest of all the ships.

Phantom speed class is eye-wateringly fast. Did Wip3out push the PSone to its limits?

There was certainly a lot of technical innovation in Wip3out, considering the game ran at a consistent 30fps in hi-res mode within some fairly detailed environments. This was a mix of some very talented programmers on the team, a deep understanding of a console that had been available long enough for all the little development quirks and tricks to be discovered, and some very careful 3D modeling that got maximum bang out of a limited polygon count.

There's been little word on the series since Studio Liverpool's closure in 2012. Do you feel WipEout and futuristic racers as a whole still have a place in modern gaming?

Definitely – these things are usually cyclical. I wouldn’t be surprised if there are plans to resurrect the PS4 version that Liverpool were supposedly working on prior to the closure. The brand has too much value to just ignore. Perhaps something to launch along with Project Morpheus? WipEout plus VR would equal awesome.

The Pixel Empire would like to say a huge thank you to Wayne for sparing us his time and insight, amidst a busy schedule at Odobo. Here's hoping WipEout will return again soon, preferably sooner than 2097.