SUIKODEN (PS)

Released in Europe in the spring of 1997, Suikoden’s old-fashioned sensibilities likely would have counted against it at the time. 3D and polygons were in: Crash Bandicoot, Tomb Raider and the looming Final Fantasy VII had gamers’ chins a-wagging. Suddenly, sprites had become a tough sell. Time, however, has been very kind to Suikoden. What seems at the outset a fairly typical mid-nineties JRPG, soon proves itself to be anything but, in what is one of the most playable and creative role-playing games of its era.

Playing as Tir McDohl, son of an Imperial general, the early sequences revolve around the young man’s comfortable life in the capital, Gregminster. This paints a picture of life under an Imperial government that, it soon becomes apparent, has become rotten at the core. Lead by Emperor Barbarosa, thought to be under the enchantment of his malevolent magician wife Windy, his rule is typified by the connivers, bullies and opportunists who do his bidding. When one night a member of Tir’s household is attacked, he and a small entourage are forced to flee. Here is where Suikoden really starts to distinguish (and indeed define) itself.

In Suikoden, the lines between good and evil are indistinct, with the option to redeem foes and recruit thieves, liars and tricksters to your cause

Tir soon becomes involved with an underground resistance, known as the Liberation Army. Before long, they set up a base of operations on an island, in the derelict Toran Castle. The player must travel the land helping elves, dwarves, dragon riders and many others in their personal plights, enlisting the help of as many as 108 figures to the resistance cause. A good majority of these can fight in your party, whilst those who don’t, may set up shop or offer various other services within the hub of the castle.

The story, which takes its queues from Chinese literature, is far stronger and more distinctive than it initially appears. Suikoden avoids some of the more obvious RPG cliches. Because of his background, Tir isn’t popular everywhere he goes; distrust is rife, and whilst there’s always the seed of hope wrought by good deeds, the townsfolk you’ll encounter at the periphery of the Empire, are often disillusioned.

The story, which takes its queues from Chinese literature, is far stronger and more distinctive than it initially appears. Suikoden avoids some of the more obvious RPG cliches. Because of his background, Tir isn’t popular everywhere he goes; distrust is rife, and whilst there’s always the seed of hope wrought by good deeds, the townsfolk you’ll encounter at the periphery of the Empire, are often disillusioned.

You’ll meet protagonists from all walks of life, some of whom join your cause willingly, whilst others require a bit more persuasion. This might depend on whether you can track down missing items such as a war scroll, an opal ring or even a missing cat. Elsewhere, reaching a certain combat level, or having particular figures of influence already enlisted to help in your cause, might sway others. You’ll find soldiers, fishermen, washerwomen, singers, blacksmiths and thieves, and collectively they help transform your base into an incredible, bustling environment that’s incredibly satisfying and rewarding to return to.

Whilst this may sound a little expansive for an action-RPG, the core story, which typically focuses on around a dozen or so main personalities, is really good. Suikoden allows for as many as six members to fight in a party at the same time, and it’s rapid levelling system and easy to navigate systems make it a joy to use. Whilst purists may dislike the obvious imbalance of having a level 10 character catch up to a level 30 character in just six or seven battles, it does encourage you to try a broad array of fighters, and not settle for a small core of ever-presents. Two lines of three means a front row of short-range, physical characters, and a back row of archers, mages and the like, offering a significant array of tactics.

Whilst this may sound a little expansive for an action-RPG, the core story, which typically focuses on around a dozen or so main personalities, is really good. Suikoden allows for as many as six members to fight in a party at the same time, and it’s rapid levelling system and easy to navigate systems make it a joy to use. Whilst purists may dislike the obvious imbalance of having a level 10 character catch up to a level 30 character in just six or seven battles, it does encourage you to try a broad array of fighters, and not settle for a small core of ever-presents. Two lines of three means a front row of short-range, physical characters, and a back row of archers, mages and the like, offering a significant array of tactics.

FOCAL POINT: LIBERATION HQ

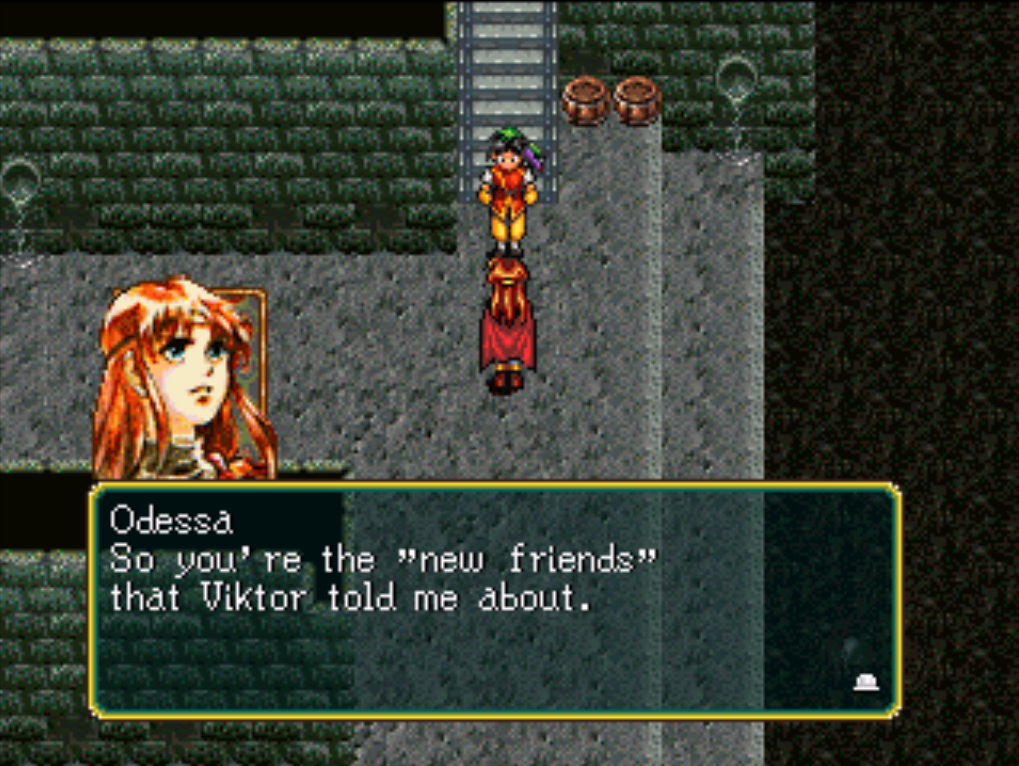

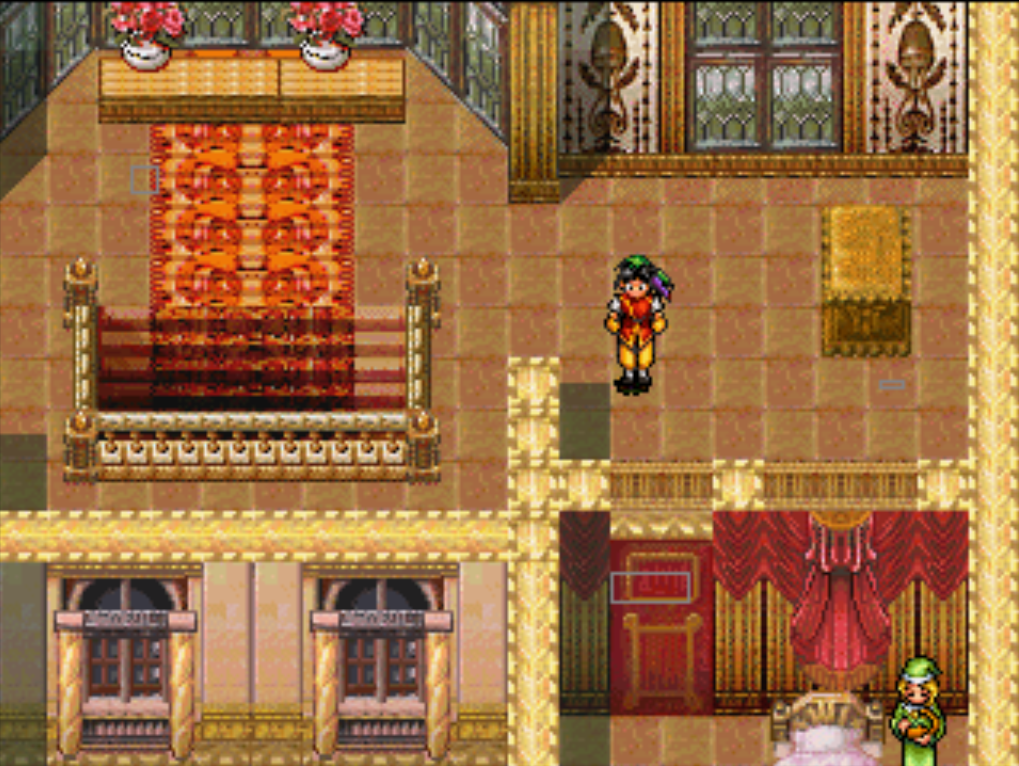

If there’s a more satisfying feature in an RPG than the Liberation headquarters, I’m struggling to think of it. Each of the 108 recruitable ‘stars of destiny’ will end up stationed somewhere within your castle, whilst winning army battles will expand the layout of your base of operations. Not only can Tir talk with all of those who’ve enlisted, but a great many provide specific services. A librarian helps make sense of books discovered throughout the game. Singers and musicians offer the chance to listen to specific BMGs or change sound effect settings. As well as a complete array of shops, blacksmiths and the like, you’ll also be able to challenge gamblers to various games of skill and chance. Suffice to say, by the end of your journey, the Castle is almost unrecognisable. It’s a far cry from first meeting Odessa in a squalid sewer and a perfect symbol of the cause’s growth.

Army battles, which are simplified strategy efforts, are especially significant. The more characters you enlist, the more troops and the more options at your disposal. Simple options such as charge, bow attack and magic are easy to grasp and are complemented by auxiliary options, such as using spies to determine the enemy’s next move or attempting to get some of them to defect. These are fun and easy to grasp, though opting for the wrong strategy at the wrong time has its consequences: unusually for the time, some of your allies can die in battle.

Suikoden is a beautiful game, and beneath its old-school sensibilities lies some surprisingly advanced visual tricks. In particular, translucency effects that make for some striking reflections in marble flooring, whilst stained glass windows, shadows and ghostly apparitions also benefit from this technical mastery. The game’s elaborate, 48-track soundtrack is an absolute cracker. There’s a medieval flavour to some of the towns with lutes, flutes and string-heavy arrangements distinguishing it from its peers. Flourishes of Japanese, Chinese and Indian cultures make for a memorable, melody-heavy arrangement that will have you humming along (even if, as with the Liberation HQ theme, it’s quite unwillingly). Gregminster’s theme is an absolute classic, but perhaps the finest piece of music is “Dwarf mines”, an anthemic effort with booming drums and bombastic horns. Close your eyes, and there are inescapable parallels with Final Fantasy VII, and that’s never a bad thing.

There’s just a couple of small gripes. Given that there are dozens and dozens of characters, the extremely modest inventory capacity for each can be a pain. It makes sense when you’re travelling, and encourages a bit of planning, which is all fine. However, trying to recall which of fifty-odd characters ended up in possession of an important item early in your quest can be a significant time-sap, even if there is the ability to deposit items at HQ. Similarly, the option to pass full sets of equipment along would have been nice, as it can feel like you’re constantly having to spend resources buying helmets and armour for a conveyor belt of recruits. Suikoden is at its best when it keeps things simple, like with its weapon upgrades. Blacksmiths sharpen weapons, boosting their power statistics with each level. Mercifully, this spares you the task of carting around dozens of obsolete weapons.

Suikoden is a beautiful game, and beneath its old-school sensibilities lies some surprisingly advanced visual tricks. In particular, translucency effects that make for some striking reflections in marble flooring, whilst stained glass windows, shadows and ghostly apparitions also benefit from this technical mastery. The game’s elaborate, 48-track soundtrack is an absolute cracker. There’s a medieval flavour to some of the towns with lutes, flutes and string-heavy arrangements distinguishing it from its peers. Flourishes of Japanese, Chinese and Indian cultures make for a memorable, melody-heavy arrangement that will have you humming along (even if, as with the Liberation HQ theme, it’s quite unwillingly). Gregminster’s theme is an absolute classic, but perhaps the finest piece of music is “Dwarf mines”, an anthemic effort with booming drums and bombastic horns. Close your eyes, and there are inescapable parallels with Final Fantasy VII, and that’s never a bad thing.

There’s just a couple of small gripes. Given that there are dozens and dozens of characters, the extremely modest inventory capacity for each can be a pain. It makes sense when you’re travelling, and encourages a bit of planning, which is all fine. However, trying to recall which of fifty-odd characters ended up in possession of an important item early in your quest can be a significant time-sap, even if there is the ability to deposit items at HQ. Similarly, the option to pass full sets of equipment along would have been nice, as it can feel like you’re constantly having to spend resources buying helmets and armour for a conveyor belt of recruits. Suikoden is at its best when it keeps things simple, like with its weapon upgrades. Blacksmiths sharpen weapons, boosting their power statistics with each level. Mercifully, this spares you the task of carting around dozens of obsolete weapons.

The main adventure will last somewhere between 20 and 25 hours, whilst attaining all 108 ‘stars’ will likely see play time creep above the thirty-hour mark. Not bad, but perhaps not quite up with the best of the best? Well, perhaps. Part of the reason Suikoden can be polished off so smartly is that it’s a wonderfully briskly-paced role-playing game. There’s a tremendous flow to it all. Loading times are minimal, screen transitions likewise. Random battles help retain the game’s exciting tempo, rather than interrupt it. To say it’s addictive would be an understatement; there are points when you’ll lose hours, and not want to put down the pad.

Suikoden rewards good deeds, providing a modest variety of outcomes depending on your treatment of others and whether you manage to enlist the help of all 108 stars (this takes some doing). Like the very best games, going the extra mile for Easter eggs and rewards feels worth it, because exploring so often yields results. It’s a model example of why role-playing games of the time have such an ardent following, and why so many since have lived in the shadow of the genre’s glory days.

Suikoden rewards good deeds, providing a modest variety of outcomes depending on your treatment of others and whether you manage to enlist the help of all 108 stars (this takes some doing). Like the very best games, going the extra mile for Easter eggs and rewards feels worth it, because exploring so often yields results. It’s a model example of why role-playing games of the time have such an ardent following, and why so many since have lived in the shadow of the genre’s glory days.

MORE CLASSIC JAPANESE PLAYSTATION RPG REVIEWS